Warning: Trying to access array offset on value of type bool in /home/daneciolino/public_html/lalegalethics/wp-content/plugins/footnotation/footnotation.php on line 193

A lawyer’s use of the word “n*****” inside of her home may be undignified, but it is not grounds for lawyer discipline according to a recent recommendation of a Louisiana Disciplinary Board Hearing Committee. See In re Odinet, Doc. No. 22-DB-039, Report of Hearing Committee No. 5 (January 23, 2023).

The Facts

During the early morning hours on December 11, 2021, Judge Michelle Odinet traveled from her Lafayette home to pick up her college-aged children and their friends from downtown. Upon returning home, she and her children came upon a burglar rifling through one of the trucks in their driveway. Over Ms. Odinet’s objection, her sons unlocked the doors of her moving car and bolted out to catch the burglar. Meanwhile, Ms. Odinet parked her car, ran inside and frantically yelled for her husband to come to the front of the house. When she returned outside, she found that her sons had tackled the burglar on the front lawn. Shortly thereafter, the Lafayette police arrived, disarmed the burglar (of a knife), and placed him under arrest.

Several hours later, after daybreak, Ms. Odinet watched a home security video of her sons capturing the burglar. While watching the video, there was a narration of what had occurred earlier. During that narration, one of the viewers recounted that Ms. Odinet had yelled a profanity—the N-word “n****r”—while she was inside of her home rushing to wake her husband. That narration was recorded on a cell phone and later posted on the Internet without her knowledge or permission.

When these events occurred, Ms. Odinet was serving as a judge in Lafayette City Court. After the cell-phone video became widely publicized, Ms. Odinet consented to interim disqualification from the bench without pay. Shortly thereafter, she resigned. Her resignation became effective on December 31, 2021.

Formal Charges

Following her resignation of office, the ODC filed formal charges against Ms. Odient alleging that her use of the racial slur violated Canon 1 and Canon 2A of the Louisiana Code of Judicial Conduct and Rule 8.4(a) (violate or attempt to violate the Rules of Professional Conduct) and Rule 8.4(d) (engaging in conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice) of the Louisiana Rules of Professional Conduct. See La. Rules of Prof’l Conduct, r. 8.4(a); id. at 8.4(d).

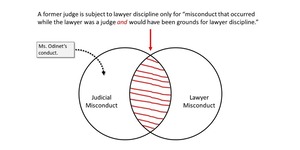

The Louisiana Supreme Court Rules are clear on when a former judge’s conduct can provide the grounds for professional discipline as a lawyer. Louisiana Supreme Court Rule XIX § 6(B) unambiguously provides that a former judge is subject to discipline for “misconduct that occurred while the lawyer was a judge” only when the conduct “would have been grounds for lawyer discipline.” See La. Sup. Ct. r. XIX § 6(B) (emphasis added). Under this rule, a former judge can be disciplined as a lawyer only for “misconduct that occurred while the lawyer was a judge” and when that misconduct “would have been grounds for lawyer discipline.”

The hearing committee found that Ms. Odinet’s conduct violated the Code of Judicial Conduct and would have provided grounds for judicial discipline. See In re Odinet, No. 22-DB-039 at 10. However, it found that her utterance did not provide grounds for lawyer discipline. See id. Under the Rules of Professional Conduct, no lawyer would be or could be subject to discipline for uttering a profane word in the privacy of the lawyer’s home on a weekend in a context completely unrelated to the practice of law. Indeed, there is no reported case of discipline being imposed on a lawyer for such conduct in Louisiana or anywhere else.

The committee also noted that no provision of the Louisiana Rules of Professional Conduct prohibits a lawyer from using offensive language at home in a context unrelated to the practice of law. See id. at 11. The only rule that might possibly have applied to Ms. Odinet’s profane utterance—ABA Model Rule 8.4(g)—was deliberately rejected by the Louisiana Supreme Court. But even if the court had adopted that model rule, Ms. Odinet would not have violated it. ABA Model Rule 8.4(g) provides as follows:

It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to engage in conduct that the lawyer knows or reasonably should know is harassment or discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, national origin, ethnicity, disability, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status or socioeconomic status in conduct related to the practice of law.

ABA Model Rule of Prof’l Cond. r. 8.4(g). By its plain terms, Model Rule 8.4(g) applies only to conduct “related to the practice of law.” Id. Ms. Odinet’s use of an offensive word on a weekend in her own home and in a setting entirely unrelated to the practice of law would not be “grounds of lawyer discipline” under this (unadopted) model rule.

The Office of Disciplinary Counsel also argued that Ms. Odinet’s speech violated Rule 8.4(d) because it was prejudicial to the administration of justice. However, the hearing committee rejected this argument. See id. at 14. Ms. Odinet did not engage in conduct “prejudicial to the administration of justice” in violation of Louisiana Rule of Professional Conduct 8.4(d) by using an offensive word in her home. Indeed, her profanity did not bring about the result proscribed by this “offense,” namely, “prejudice to the administration of justice.”1 Ms. Odinet uttered a profane word at her home; not at a law office or courthouse. She did so on a weekend; not on a workday. A third party broadcast her profanity to the public without her knowledge or consent; she did not. Most importantly, after publication of the profanity, then-judge Odinet presided over no cases and signed no judgments or orders that could have been prejudiced by anything she said earlier at home. Instead, she promptly consented to an interim disqualification from judicial office and thereafter resigned. For these reasons, it is impossible that her profane utterance was a cause-in-fact of “prejudice” to the administration of justice—either in general or in any particular civil or criminal action.

Conclusion

In full disclosure, we represented Ms. Odinet in these disciplinary proceedings. While we believe that her use of the word “n*****” was inappropriate and undignified, we firmly believe that a lawyer does not commit professional misconduct by using a racial slur in the privacy of her own home. The hearing committee agreed. So, what happens next? Ms. Odinet’s case now heads to the Louisiana Attorney Disciplinary Board for briefing and oral argument. Whether the LADB—and ultimately the Louisiana Supreme Court—will agree with the hearing committee remains to be seen. Stay tuned.

- Thus, the offense defined in Rule 8.4(d) is a “result” offense—not a “conduct” offense. See generally Walter W. Cook, Act, Intention and Motive in the Criminal Law, 26 Yale L.J. 645, 646-48 (1917) (noting that “act” component of an offense captures three elements—the specific action, the muscular movements, and the attending circumstances); Paul H. Robinson & Jane A. Grall, Element Analysis in Defining Criminal Liability: The Model Penal Code and Beyond, 35 Stan. L. Rev. 681, 691-99 (1983) (explaining that culpability terms are defined in relation to conduct, attendant circumstances, or results). The result element, conduct element, and attendant circumstance element are sometimes referred to as the components of the “social harm” portion of the actus reus (as opposed to the voluntary-act portion of the actus reus). An “attendant circumstance” is a condition that must be present along with the prohibited conduct or result thereof in order to constitute the actus reus of the offense. The meanings of the terms “result” and “conduct” are obvious. To illustrate these components, the crime of vehicular homicide in Louisiana contains a result element (death of a human being), a conduct element (operating a vehicle), and an attendant circumstance element (while “under the influence” of drugs or alcohol). See La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 14:32.1(A). ↵