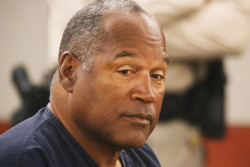

A Nevada federal district court refused to dismiss a lawyer’s breach of contract claim against another lawyer for their failure to comply with the fee-sharing provisions of Rule 1.5(e). See Grasso v. Galanter, No 2:12-cv-00738 (D. Nev. Sep. 20, 2013). In most jurisdictions (including Louisiana and Nevada), Rule 1.5(e) requires a written agreement with the client as a prerequisite to dividing fees among lawyers in different firms. The plaintiff in Grasso—who served as local counsel in the unsuccessful defense of O.J. Simpson’s 2008 robbery charges in Las Vegas—entered into no such written agreement with Simpson and lead counsel Yale Galanter when the lawyers agreed to split Simpson’s fixed fee one-third/two-thirds. When Grasso sued Galanter for breach of contract, Galanter filed a motion to dismiss the claim due to noncompliance with Rule 1.5. Rejecting this defense, the court ruled:

A Nevada federal district court refused to dismiss a lawyer’s breach of contract claim against another lawyer for their failure to comply with the fee-sharing provisions of Rule 1.5(e). See Grasso v. Galanter, No 2:12-cv-00738 (D. Nev. Sep. 20, 2013). In most jurisdictions (including Louisiana and Nevada), Rule 1.5(e) requires a written agreement with the client as a prerequisite to dividing fees among lawyers in different firms. The plaintiff in Grasso—who served as local counsel in the unsuccessful defense of O.J. Simpson’s 2008 robbery charges in Las Vegas—entered into no such written agreement with Simpson and lead counsel Yale Galanter when the lawyers agreed to split Simpson’s fixed fee one-third/two-thirds. When Grasso sued Galanter for breach of contract, Galanter filed a motion to dismiss the claim due to noncompliance with Rule 1.5. Rejecting this defense, the court ruled:

Despite Defendant’s assertion otherwise, the Nevada Supreme Court, in Shimrak v. Garcia-Mendoza, addressed this issue and indicated that an attorney is not permitted to use his own violation of the ethics rules to shield himself from contractual liability. 912 P.2d 822, 826 (1996) (the Court found it would be inequitable to allow the attorney to benefit from free investigative services because he violated the ethical rules).

For these reasons, Defendant has failed to establish that Plaintiff’s Complaint is defective. Therefore, the Court denies Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss regarding Plaintiff’s breach of contract cause of action.

See id.

This opinion is the latest in a mixed-bag of reported decisions around the country addressing this issue. It is clear that an unethical fee-sharing agreement between lawyers may subject them to discipline. It remains less clear whether the unethical nature of the agreement will bar its enforcement as between the parties. The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit has held that an agreement to divide fees is unenforceable if the agreement violated the applicable professional conduct rules. See Kaplan v. Pavalon & Gifford, 12 F.3d 87 (7th Cir. 1993); see also Kelley v. Donohue, 907 P.2d 458, 465 (Alaska 1995) (following Kaplan); see also Lemond v. Jamail, 763 S.W.2d 910 (Tex. Ct. App. 1989) (holding that fee-splitting agreement was void because it violated public policy). But see King v. Housel, 556 N.E.2d 501 (Ohio 1990) (lawyer estopped from claiming that fee-splitting agreement was invalid). See generally Joseph M. Perillo, The Law of Lawyers is Different, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 443, 447-48 (1998) (arguing that under the Restatement of the Law Governing Lawyers, courts have “total discretion” as to whether a lawyer is entitled to compensation despite violation of disciplinary rules).

Some Louisiana courts have permitted lawyers to share fees in an amount in proportion to the services rendered when the lawyer’s fee-division agreement did not comport with Louisiana Rule of Professional Conduct 1.5. In Dukes v. Matheny, the Louisiana First Circuit Court of Appeals held as follows:

[Louisiana] courts have declined to apply the joint venture theory to support an equal division of the fee when the attorneys have not been jointly involved in the representation of the client. See Brown v. Seimers, 726 So. 2d 1018 (La. Ct. App. 5th Cir. 1999); see also Matter of P & E Boat Rentals, Inc. v. Martzell, Thomas & Bickford, 928 F.2d 662, 665 (5th Cir.1991). Rather, the apportionment of the fee in those types of cases has been based on quantum meruit. Brown, 726 So. 2d at 1023. Such a ruling is in accord with Rule 1.5(e) of the Rules of Professional Conduct . . . .

Dukes v. Matheny, 878 So. 2d 517 (La. Ct. App. 1st Cir. 2004); see also Chimneywood Homeowners Ass’n, Inc. v. Eagan Ins. Agency, Inc., 57 So. 3d 1142, 1152 (La. Ct. App. 4th Cir. 2011); Bertucci v. McIntire, 693 So. 2d 7, 9 (La. Ct. App. 5th Cir. 1997); Huskinson & Brown, LLP v. Wolf, 84 P.3d 379, 385 (Cal. 2004) (stating that noncompliance with ethics rules invalidates firms’ agreements to divide fees but does not forbid quantum meruit action). However, at least one Louisiana appellate court declined even to consider the merits of a claim that a lawyer in violation of the Rules may be subject to fee forfeiture. See Brown v. Seimers, 726 So. 2d 1018, 1020 (La. Ct. App. 5th Cir. 1999) (“This complaint . . . should be raised with the Bar Association”). So, it remains an open question how the Louisiana Supreme Court would resolve this issue.